Samskritam Notes: Sounds and Vibrations

The Samskritam sounds have been organized to affect the person chanting them. This comes from a deep understanding that everything in the universe is a vibration

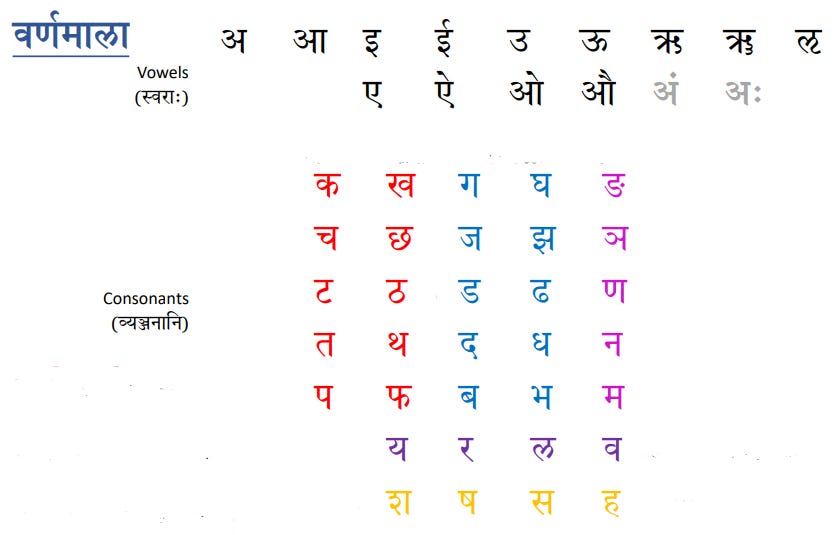

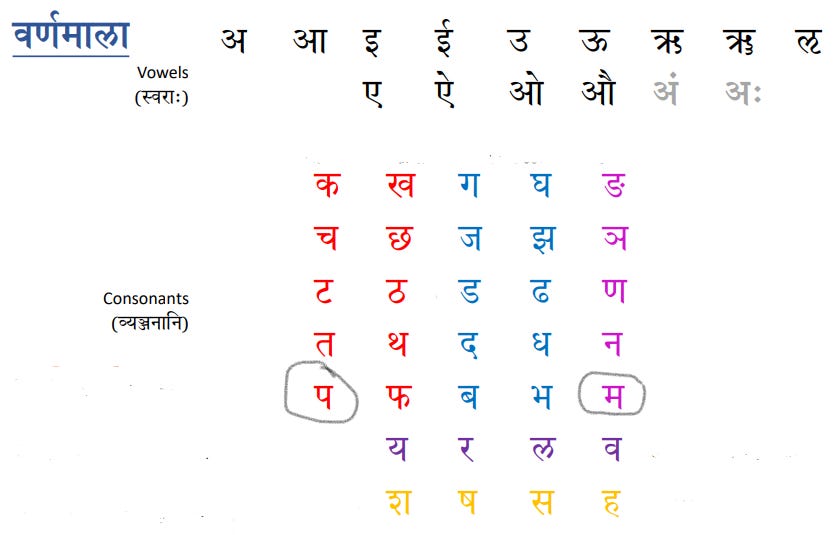

The above picture shows the organization of Samskritam varṇamālā in Devanagari script. First, there are the swaras at the top, followed by the vyañjanas. This sequence is the same in all Indian languages.

But why so? Why not in some other sequence? Why is क the first vyañjana or अ the first swara? In this article, we will look at the reason for such an organization of the aksharas. We will also see how the effects of the points of articulation were understood by Samskritam grammarians. Finally, we will also see what makes Om such a unique sound and how this ties to mantra sadhana.

Points of Articulation

This organization of aksharas is based on understanding how sounds are produced in the human mouth. In Samskritam, five areas of the mouth are important for producing various aksharas. Among these five areas, there is a progression from the back of the mouth to the front, forming the basis of the organization. The sound originates based on the contact between the tongue and these areas. Once you learn this, you will observe how the tongue shifts as you say different aksharas.

Let's go over each area and see what sounds originate there. The following picture shows our vocal system with the vital sound sources marked.

The first position is the kaṇṭah or throat. When your tongue makes contact at the back of the throat to produce those aksharas those sounds are called the kaṇṭhya. To experience this, say क and feel where your tongue hits the mouth.

The aksharas that come from there are the following.

Swaras: अ

vyañjana: कु

ushmana: ह

ayogavāha: visargah

Here अ means both अ and आ. In fact it represents 18 variations of अ (See: Classification of Letters)

Now what the heck is कु? This is a short form for क ख ग घ ङ. Instead of repeating those five vyañjana, Panini calls it कु.

To understand this short form, you have to get into the mindset of Panini. He was obsessed with brevity. If you can compress 8 bytes into 1, he would do it. In an oral tradition, there is limited memory, and you need to find ways to abbreviate. This kind of brevity helps develop a sutra to make it easy to remember. In this case, you can remember the sutra अ-कु-ह-विसर्जनियानां कण्ठः Look at the first three characters of the sutra - अ कु and ह. Then it adds the visarga and says all of these come from the kaṇṭah.

As you move up from kantah, you reach the talu at the back of the mouth. This is the place where your tongue touches your back teeth. To feel this, try saying इ very slowly and see how your tongue stretches at the back and pushes against the back teeth. talu is the pressure between the tongue and the upper back teeth.

The following sounds come from the tālu and are called the tālavya.

swaras: इ

vyañjana: चु

antastha: य

ushmana: श

Try saying च. Do you feel the contact of the tongue at the front of the mouth or the back? It feels like the front. If you are not feeling that pressure, you are not pronouncing it correctly. Next time pay attention. If you are going to events like Gita Chanting Competition, this will help.

The next spot in the mouth is the murdha. This is the roof of your mouth. These sounds originate when your tongue touches the top of the mouth. Try saying ट, and you can feel it. These are the mūrdhanya sounds.

swaras: ऋ

vyañjana: टु

antastha: र

ushmana: ष

The next place in your mouth is where the tongue hits the teeth. They are called the dantya

swaras: ऌ

vyañjana: तु

antastha: ल

ushmana: स

Now you can see the pattern here.

Finally, when the contact happens at the lips, it is called the oṣṭhya.

swaras: उ

vyañjana: पु

What's left now? ए ऐ ओ औ and व. These come from a combination of two places in the mouth.

ए and ऐ come from both kantah and talu. Hence it is called kantatalu. The best way to experience this is to say अ (kantah) and इ (talu) really fast. Then, you will end up saying ऐ. Now, if you start saying अ and slowly transition to इ, somewhere in the middle, it will transition to ए. That's why it is known as kantatalu. ए and ऐ have some proportion of अ and इ and is actually a combination letter.

ओ and औ are produced by a combination of kantah and oshtah. Hence it is called kanṭhoṣṭhya. The same process applies here as well. Say अ (kantah) and उ (oshtah) really fast. You will say औ. If you start at अ and slowly transition to उ, you will say ओ. Remember how we saw that ए and ऐ have some proportion of अ and इ. Similarly, ओ and औ have some proportion of अ and उ.

Finally, what's left is व. That's a combination of dantah and oshtah. So it is a dantoṣṭhya.

Going back to our original layout of letters, we now see the format based on the points of articulation.

Nāsikā

There are one more places where sounds come from. The nose. There are five nasal sounds in the varṇamālā, the last five letters in the pillar. ङ ञ ण न म They are also called nāsikā.

But didn't we say that these letters originate in various other places? So these letters need the original place in the vocal and the nose.

Anuswara & Visarga

What about the anuswara and visarga. The anuswara is just a nasal sound and takes on a variation of the vyañjana that follows it. Let's look at the word संपदः. The anuswara is above स. Look at the vyañjana that follows स. That is प. Now in the varṇamālā, find the location of प. Move your finger all the way to the right, and you hit म.

The sound of anuswara becomes the sound of the vyañjana in the fifth column. Hence the word gets pronounced as sam-pada.

visarga is just the release of the breath. So, for example, if you have the word हरिः, then the ending इ remains as-is, and you release your breath.

Sounds and Vibrations

In Samskritam pronunciation, there is a conscious use of the breath. For example, say क followed by ख and watch the breath pattern. (If you did not feel any difference, you might not be saying ख with intensity). This is like a natural pranayama. Look at the breath pattern when you do the visargah. It is like a sigh, a natural de-stressor. If you take a swara like अ, there are 18 ways to say it with varying breath patterns. (See: Classification of Letters) Due to these varying breath patterns, there is a physiological impact on you. Like when you chant a mantra.

Thus these sounds don't exist in isolation; they create an experience. Specifically, specific sequences have an impact on the mind and the body. For example, there is a systematic way in which the tongue touches the vocal system. This, in turn, causes the nerve endings to be simulated and hence the corresponding brain regions. The science of mantra believes that if you can use the right words to train your mind, sharpen its focus, and to channelize the divinity in the universe, you can rise above every negative tendency that holds you back and go past the shackles of your limited conscious mind.

Look at the mantra Om. It is made up of three sounds अ उ and म. अ starts at the throat and is the first swara the human vocal system can produce. उ comes from the lips and is the last swara the vocal system can make. Going from अ to उ covers the entire range of the vocal system. The final म is the settling down or containment of the sound produced.

Chanting Om is a mantra sadhana. Aurobindo says, "The function of a mantra is to create vibrations in the inner consciousness that will prepare it for the realization of what the mantra symbolizes and is supposed indeed to carry within itself."

The basic principle of mantra sadhana is to practice the utterance of a sound with such intensity, fervor, and determination, that your whole being starts reverberating with that sound. You become that sound, and that sound transports you to another dimension of consciousness. Mantra is a systematized sound technology. The Samskritam sounds have been organized to affect the person chanting them. This comes from a deep understanding that everything in the universe is a vibration. The rishis knew that certain benefits could be achieved by creating those vibratory patterns through our vocal system.

References

Lecture by Varun Khanna at Chinmaya International Foundation.

The Sounds of Sanskrit: Its Alphabet by Prof. Anuradha Chowdry at IIT Kharagpur

The Ancient Science of Mantras: Wisdom of the Sages by Om Swami.

Postscript

The technical term for replacing क ख ग घ ङ as कु is udit

Wonderful article on the science of the Sanskrit aksharas. So many people confuse 'akshara' (the primal sound unit) with alphabet which is the written representation unit and can be in a variety of scripts. What is extremely interesting is the similarity of the patterns of most pan-Indian languages in terms of the classification identical to the Sanskrit aksharamala. This extends beyond India in several cases.

Another interesting aspect is the use and codification of these sounds for data preservation and transmission over millennia which I wrote about here -> https://itihaasa.substack.com/p/the-science-of-phonetics-siksa-vedanga

The Vedic sound classification is one aspect where the pronunciation is given maximum importance. In the later classical Sanskrit especially after Panini's codification in the Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit essentially became the only spoken language with a meta-language where you could create words from their roots using an applied set of rules. This is fairly complex computing by the human mind and is another important key for Sanskrit being amara (immortal) and hence being called Devabhasha.